Reimagining Water Governance in South Asia: Beyond Borders

𝐃𝐫. 𝐀𝐫𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐊𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐫,

𝐏𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭, 𝐈𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐚 𝐖𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐅𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

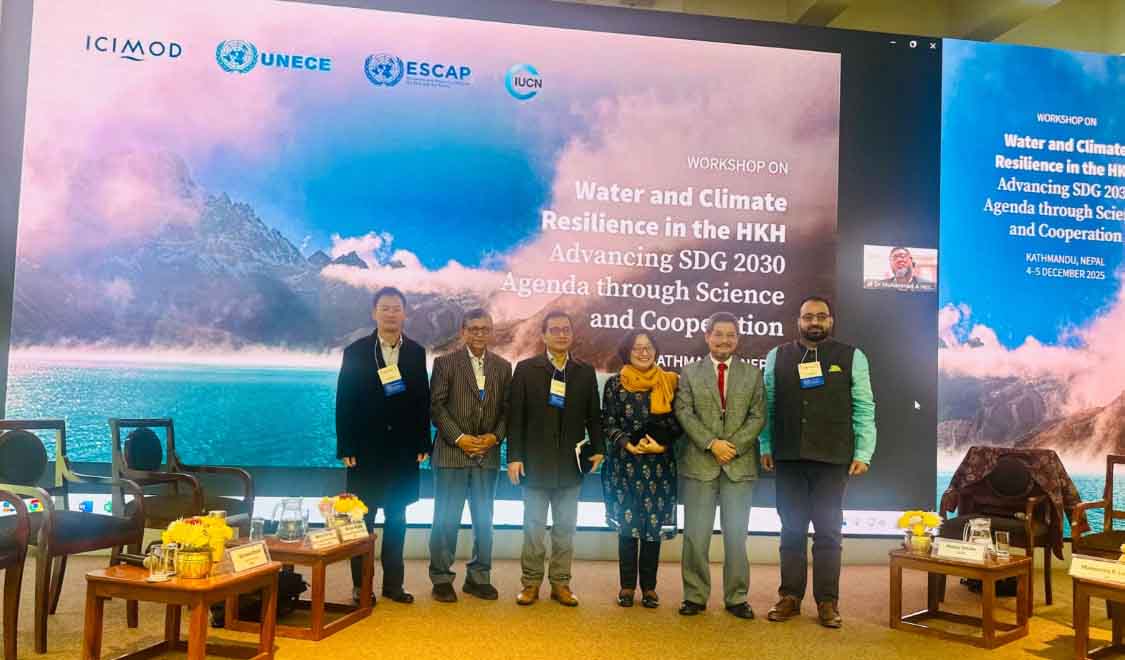

“South Asia must learn to see itself as a shared hydrological and socio-economic space rather than an assortment of isolated national water economies” was something I stressed on during the round table organised by UN ESCAP on Roundtable on Water–Climate Nexus national perspectives as part of the HKH Water & Climate Resilience Workshop held in Kathmandu on 4–5 December 2025, organised by UNESCAP in collaboration with ICIMOD, UNECE, and IUCN.

The Hindu Kush Himalayan (HKH) region stands today at a critical crossroads in an era when climate volatility and water insecurity are reshaping global priorities. As the world’s “Third Pole” and the source of ten major river systems that sustain nearly two billion people, its future is inseparable from South Asia’s collective resilience. This understanding was central to the deliberations which reaffirmed a truth we can no longer ignore: climate and water risks in our region transcend borders, institutions and sectors. Our responses must do the same.

Across India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan and beyond, scattered but powerful examples demonstrate what resilience can look like spring-shed revival and watershed development in the Himalayas, more efficient irrigation practices, community-managed flood shelters, and early warning systems that have saved thousands of lives. But these successes are islands in a sea of fragmentation.

Our water governance remains compartmentalised across ministries. Planning often relies on averages rather than risk scenarios, because data on water quantity, quality, sediment loads, hazards, ecosystem decline is incomplete, inaccessible or not shared. Urbanisation is advancing with little regard for river corridors. Floodplains are encroached, wetlands degraded, sand mined, and aquifers overdrawn. Climate change magnifies each of these pressures, hitting the poorest households, informal workers and marginalised communities first and hardest.

Charting a Shared Future

In Kathmandu, one message stood out that the most effective solutions in South Asia emerge when scientific tools converge with traditional knowledge and local institutions. Community irrigation systems, participatory groundwater management, village-led water security planning and climate-smart agriculture are not peripheral experiments, they are proven pathways. What they require is financial support and integration into national strategies.

Transboundary cooperation must now become the backbone of our regional resilience architecture as Ganga, Brahmaputra and Indus do not recognise political boundaries. Strengthening cross-border data-sharing, joint research, basin-level dialogues and coordinated flood and drought management is no longer aspirational- it is foundational.

Any conversation on resilience must also acknowledge the voices historically left behind. Migrants, Indigenous communities, women, youth, and those living in fragile geographies face the sharpest edge of water and climate risks yet remain peripheral to planning. Their participation cannot be symbolic. Women, who bear primary responsibility for household water security, must be embedded in decision-making roles in disaster management and local water committees. Youth can serve as the region’s climate and water stewards if supported through training, innovation ecosystems and community-linked enterprises. Recognising and honouring their agency is not a matter of inclusion alone; it is a strategic necessity for long-term resilience.

Equally, ecosystem-based solutions must be treated as core investments; wetland restoration, mangrove regeneration, riverbank stabilisation, spring-shed revival and catchment treatment deliver enduring co-benefits for biodiversity, livelihoods and carbon sequestration. These are not “soft options”; they are scientifically grounded interventions that strengthen resilience at a fraction of the cost of grey infrastructure. The workshop’s outcome rightly emphasises that cryosphere loss in the HKH is accelerating at a pace that demands urgent, coordinated action. It called for harmonised monitoring networks across basins, basin-wide hazard and loss databases, interoperable data systems, and climate-informed design standards for infrastructure.

What emerges from Kathmandu is clear; the HKH region needs a unified voice, grounded in science, inclusive in character, and cooperative in spirit. As we approach APFSD 2026 and the 2026 UN Water Conference, South Asia has an opportunity to demonstrate leadership not merely by articulating its vulnerabilities, but by advancing a credible blueprint for river-basin resilience. For the HKH, the path ahead must place ecosystems, equity, community institutions, and regional solidarity at its centre. Only then can we chart a future where our rivers remain living systems and our people secure, empowered and resilient in the face of a changing climate.